ILLUSTRATION: ELENA SCOTTI/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL, ISTOCK

How CD Rates Can Go From High to Low While You're Not Looking

John Furlong signed up for a certificate of deposit last year that paid 3.85%. When he checked his account in February, he was surprised to find the bank was only paying him 0.05%.

The 62-year-old construction manager thought there was a mistake. Then an employee at his branch in Henderson, Nev., told him that his $50,000 CD had matured and automatically rolled into a new one that was paying a lower rate. The only way to get out of the low-rate CD was to pay an early withdrawal fee

“It’s fool’s gold,” he said. His money is earning $2.15 a month until the new CD matures in October, instead of the $160 he had been collecting.

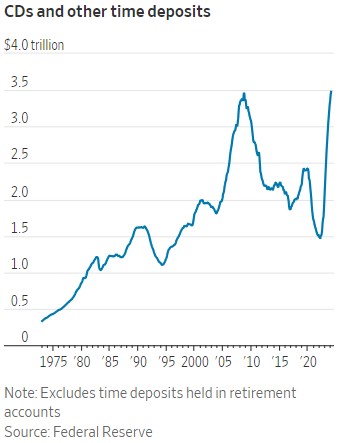

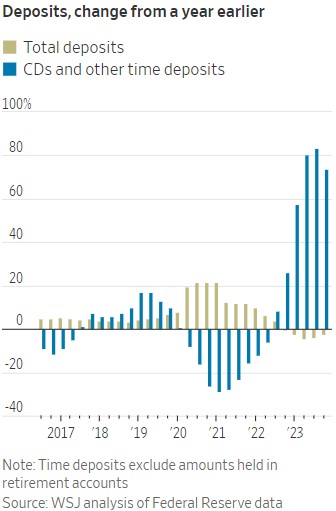

Americans poured more than $2 trillion into CDs to lock in higher interest rates since the Federal Reserve began raising its own rates in 2022. When CDs mature, roughly half of them are automatically rolled into new bank-issued CDs and locked up again, according to data and consulting firm Curinos.

Customers are finding that some of those new CDs come with rates that pay much less than the old ones.

Cash investments, some of the biggest opportunities of the high-rate era, aren’t always living up to their advertising. Some banks have also left customers in savings accounts with low rates, while advertising high yields to draw new customers.

CDs can offer some of the highest rates on cash because customers agree to lock up their money for say, six months or two years. By contrast, savings and money-market accounts can change their rates at any time.

Automatic Roll

Roughly half of all new deposits flowing into banks since the start of 2023 have been CDs, according to Curinos.

When the account is maturing, the bank is required to notify customers. If the CD will automatically roll into a new one, the bank must disclose in writing the date a new interest rate will be determined. But under current regulations, they don’t need to contact customers to tell them the new rate, only provide them with a phone number to call to get the information.

Furlong didn’t call to get his new rate before his old 11-month CD with U.S. Bank matured. Before letting the CD renew, he looked online and saw the bank was advertising CDs with the same term with a rate of 4.1%.

“Shame on me for looking at what’s publicized and making assumptions,” he said.

In response to questions from The Wall Street Journal, U.S. Bank said it is changing communications around CD renewals to make it clearer to customers what rate options are available.

“We work hard to provide a positive experience for all customers and regret that this individual’s experience was not satisfactory,” spokesman Evan Lapiska said.

Furlong, who taught himself how to put together a CD ladder last year, now has a digital calendar to track important dates for his half-dozen CDs across different banks.

A Forgotten Investment

Historically, CDs have represented a small share of all deposits. Banks haven’t paid much attention to them because their customers didn’t, so the recent surge in demand caught many banks flat-footed, said Adam Stockton, managing director at Curinos, which tracks deposit trends.

The renewal process in particular has become a pain point across the industry. “They’re certainly hearing it from customers,” Stockton said.

Banks could notify customers of their new interest rates without regulations requiring them to do so, but many don’t, said Ken Tumin, founder of DepositAccounts.com, a website owned by LendingTree that tracks banks’ account offerings. When CDs are renewed at less-than-competitive rates, banks can keep the difference between the old rate and the new one.

Many of the CDs opened over the past year offered what are considered special or promotional rates, which are unlikely to be automatically matched at renewal, Tumin said. CDs with unusual terms, like seven, 11 or 13 months, are more likely to fit that category.

“Everyone’s busy, and it’s easy to forget. And, if you do forget, often the bank wins,” Tumin said.

CDs have grace periods—usually between seven and 14 days—that allow customers to move money from the account. After that, there is typically a penalty to withdraw the money, such as a percentage of interest earned or a portion of the original investment.

In addition to selling CDs directly, banks also offer them through third-party brokerages, often at higher rates. Many sold more brokered CDs to shore up their deposit bases after last year’s banking crisis. The brokerages tend not to auto-renew customer CDs and instead deposit the money into a money-market account.

Some customers are finding that banks can be more lenient about auto-renewals than they say, especially for those willing to make a stink about it.

Michael Cammer threatened to complain to a state regulator after his 2.35% five-year CD renewed at an interest rate of 0.01% last summer. He went to his local Webster Bank branch in the New York City suburbs and walked out with a check for his full balance—no fees subtracted. The money is now earning 4% elsewhere.

“I don’t know if they would have done it with a less aggressive person, but I made it clear we weren’t paying any fees and they didn’t argue with us,” Cammer said.

Original Article: "How High-Yield CDs Turn Into 0.05% CDs While You’re Not Looking", WSJ